All physicists are taught that quantum measurements destroy coherence. Yet, if performed with care they can preserve coherence and even manipulate quantum states.

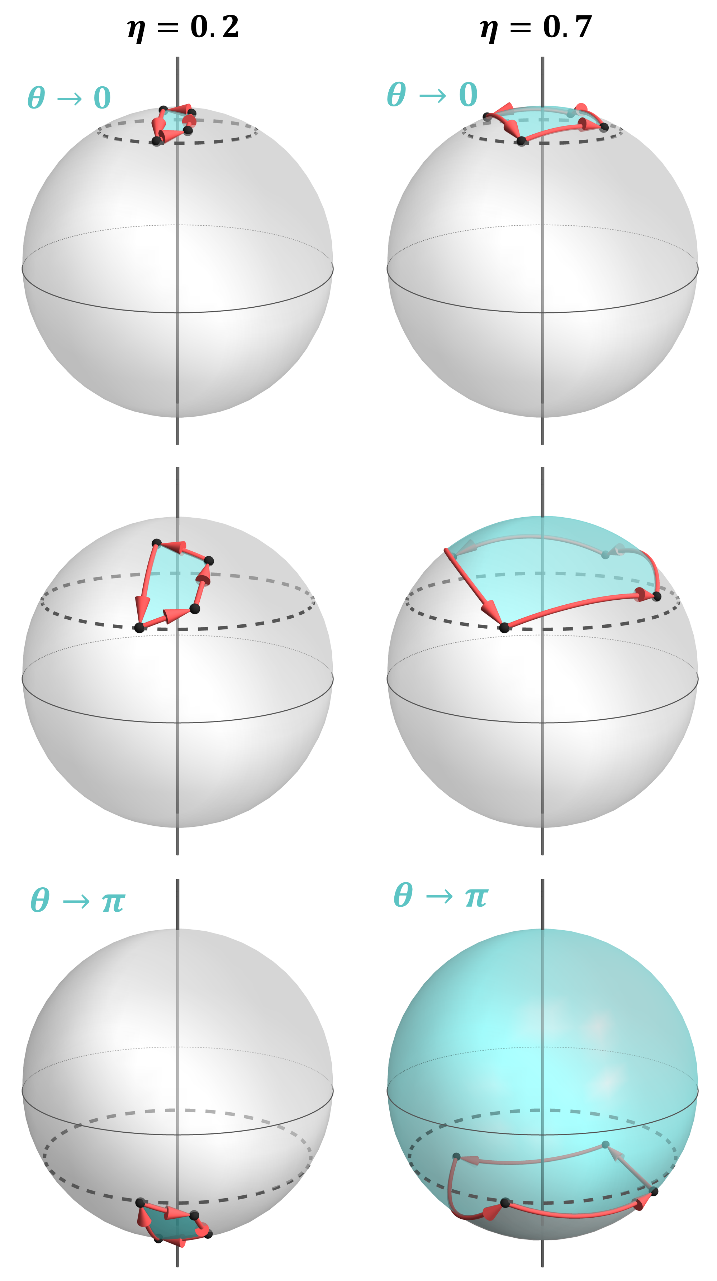

The researchers from PHELIQS/GT [Collaboration] investigated geometric phases induced by quantum measurements and found that these may behave in drastically (topologically) different ways under protocols employing strong or weak measurements. For weak measurements (small measurement strength: η→0; η=0.2 in Fig. 1), the qubit hardly changes its state and thus acquires little geometric phase; for strong measurements (η→∞; η=0.7 in Fig. 1), the qubit state follows extended trajectories and acquires significant geometric phase. It turns out that this distinction is not only quantitative but can be qualitative.

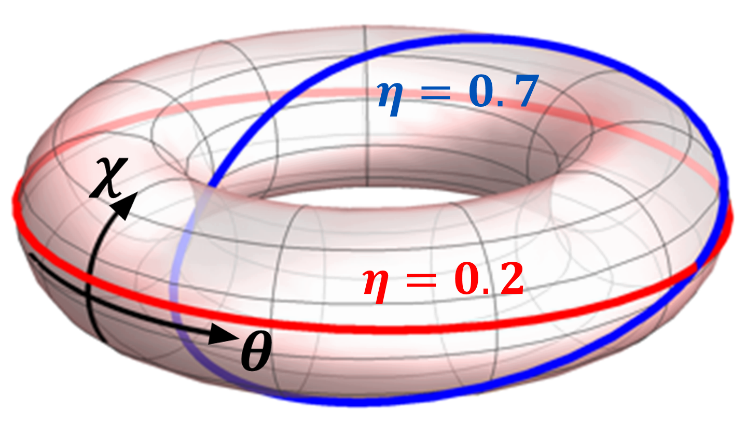

One can plot the dependence of the geometric phase χ on the protocol parameter θ on a torus with the two respective coordinates (Fig. 2). The curve for weak measurement winds around the horizontal circle on a torus, but not around the vertical one. The curve for strong measurements winds around both. A continuous deformation cannot transform one curve into another, making them topologically distinct. This automatically implies that the transition between the two behaviours is abrupt, occurring at some intermediate measurement strength.

The work has started with a number of theoretical investigations:

And now it has culminated in experimental verification of the predictions:

Geometric phases play an important role in the quantum physics of condensed matter systems. And topological properties have importance in both established applications (such as the standard for electrical resistance based on topologically quantized Hall conductance - Quantum Hall effect -

Wikipedia) and prospective technologies (Topological electronics

Communications Physics 2021).

It is hard to foresee specific applications resulting from the above works on the topological transitions of measurement-induced geometric phases. Yet these contribute to our knowledge of how quantum systems affected by their decohering environment behave. This knowledge may be valuable, in particular, when trying to perform simulations of real-world materials using quantum simulators – which are subject to decoherence/measurements by their environment.

Collaboration: the Weizmann Institute of Science (Israel), University of Freiburg (Germany), Lancaster University (UK), Washington University in St. Louis (USA), and University of Ottawa (Canada).